The Gezi Park Protests and Politics of the Family

Many academic commentators on the Gezi Park protests and the ensuing nation-wide uprisings have tended to focus on their more overtly political characteristics, adopting a macro-political perspective in their approach to the unfolding events. This essay instead diverts attention to the family, a seemingly less distinct “political” domain, and examines how state officials have utilized familial discourse during the Gezi Park events as a way to quell the protests, discredit the protestors, and define the parameters of the public sphere. Below, I detail three significant instances of politicians’ references to the family in their speeches. As these instances illustrate, lying at the heart of the neo-conservative social policies of the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP), the family stands out as a significant political category that constitutes the grounds upon which the politics of identity are played out and contested.

“Mothers and Fathers, Do Something About Your Delinquent Kids!”

Several days before the police forcefully evicted the protestors from Gezi Park and subsequently closed it to the public, Istanbul Governor Hüseyin Avni Mutlu called out the parents of the protestors in a press conference, requesting their assistance in quelling the protests by persuading their children to leave the park and come back home. The governor stated that he had “serious concerns about the safety of our kids’ lives.” According to the governor, the protestors comprised two groups: agent provocateurs who incited the well-intentioned environmentalist protestors to break the law, and naive kids oblivious to the grave dangers that these provocateurs had driven them into.

Mutlu told the protestors’ parents that, as their “uncle governor,” he loved these kids as much as his own children and advised the parents to protect their kids, their “most precious assets.” The polysemous idiom that the governor used in his advice, “Sahip çıkın!,” could mean “to attend to” or “to protect,” but it might also mean “to claim the ownership of,” or, for that matter, “Do something about that (delinquent) kid of yours!” This was not by any means the first instance in which such “parental advice” was issued by state officials to the families of protesters. For instance, the parents of the Kurdish children accused of (and subsequently jailed for) throwing stones at police officers and chanting “illegal” slogans during demonstrations have also been ordered by state officials “to keep their delinquent kids under control.”

Non-Turkish readers might find it curious that the governor would consider the Gezi Park protestors, most of whom are legal adults over the age of eighteen, “kids” or “children” in need of their parents’ and families’ guardianship. What is more ironic, however, is that some of these very same “kids” would later be deemed old enough to be detained and arrested for being members of allegedly illegal “marginal” or even “terrorist” organizations. Implicit in the governor`s reference to the protestors as “kids” and “our children,” and to himself as their “uncle,” is how politicians conceptualize their relation to their constituents in terms of familial roles. In fact, the political rhetoric of describing younger constituents as “kids,” “youth,” or “children” is nothing new. It has its roots in the Republican ethos, which has tended to view the state and its rulers as guardian parents and citizens as pedagogical subjects (hence, the founder of the republic is known as Atatürk, the father of Turks).[1]

It was not just the politicians who attributed familial roles to the subjects and objects of governance. When Erdoğan met some celebrities as part of his public relations tactic to alleviate negative publicity ensuing from his crackdown, Hülya Avşar, a famous actress and television personality, spoke to the press after her meeting with Erdoğan “as a mother raising a teenager.” She told reporters that she gave pointers to Erdoğan about how families handle a domestic dispute: “The child breaks, the mother mends, and the father looks the other way.” In Avşar’s formulation, the protestors were once more reduced to “rowdy children” whom “the father state” needed to learn to tolerate.

While the governor adopted a milder tone that was disapproving and concerned (quite apt for an uncle), the Patriarch Erdoğan’s tone was forewarning at best, if not threatening. In one of his political rallies, Erdoğan also called out the protestors’ parents and used the same expression used by Governor Mutlu: “Sahip çıkın!” He stated, “I am warning you one last time. Mothers and fathers, get your children under control (do something about your [rowdy] kids!). Otherwise, we can’t exercise restraint any longer (and will use force to keep them under control).” Erdoğan’s warning to the parents to tame their “misbehaving” and “delinquent” children constitutes almost a caricature of Michel Foucault’s conception of “political economy,” which draws parallels between the governance of a state and the running of a household. According to Foucault, “the word ‘economy’ can only properly be used to signify the wise government of the family for the common welfare of all, and this is its actual original use....To govern a state will therefore mean...exercising towards its inhabitants, and the wealth and behavior of each and all, a form of governance and control as attentive as that of the head of the family over his households and his goods.”[2] While Foucault uses this analogy for the sake of illustrating how this particular form of governance operates, through his paternalistic discourse Erdoğan has literally acted as if he were the head of a household.

Politicians’ appeals to the family are quite significant in that they also point to a particular rationality of governance whereby the family is conceptualized as both the cause of an individual’s disorderly conduct (and thus, also the site of its containment) and as the building block of society because of its pedagogical function. Underlying this rationality is the belief that the society (or the social and moral order) is at risk because the family institution is deteriorating. Thus, there would be fewer social problems (including crime) if the family were to fulfill its function in disciplining and policing the conduct of its younger members appropriately.

In fact, this rationale forms the basis of a recent project initiated by the Turkish National Police to “win back” mostly college-age young people who have allegedly become members of “illegal political and terrorist organizations.” Within this project, the police contact the parents of these “kids” and provide them free counseling on how to strengthen family ties and become good parents. The counselors in this project claim that they strongly caution parents not to tell their kids that they know of their participation in these organizations. The belief is that it is only through being members of a good and healthy family—and not through coercion—that these young people will discontinue their participation in illegal organizations. According to the report published by the National Police earlier this year, this strategy has proven to be effective: the children of seventy-six percent of the fourteen thousand families they have provided with such counseling within the past two years have dropped out of illicit organizations.

Such political rationality also deems the parents to be liable for any detriment to the safety of their children. The next day, Mutlu repeated his request for the parents to call their children home, suggesting that: “It is the parents’ responsibility to take the necessary precautions about their children’s safety.” This “responsibilization” strategy used by the governor is indicative of the neoliberalization of the Turkish polity within the past several decades, but most notably under AKP rule. In the context of the neoliberal policies implemented by the AKP government since 2002, citizens have been increasingly expected to exercise responsibility for ensuring that their family members are supported and cared for. Under neoliberal regimes, an individual’s success, security, and well-being are generally considered to be determined by his/her own habits and behavior, rather than attributing these to the political, economic, or social structure. Thus, each individual is deemed responsible and accountable for his/her own welfare, education, heath care, and security. Just as with individuals, the family as a unit is also expected to have the “moral agency that accepts the consequences of its actions in a self-reflexive manner.” Within this framework, the family is conceptualized as a self-supporting and self-regulating site of social and economic welfare, and families have increasingly been expected to conduct themselves responsibly and to account for their own lives.

The Marauder Youth and their Revolutionary Mothers

The protestors and their parents did not remain passive addressees of this political discourse, but rather actively engaged with the political actors by contesting their demands and subverting the traditional roles attributed to the family by these politicians. An anonymous group of protestors who, with reference to Erdoğan’s name-calling, call themselves “çapulcu gençler” (“the marauder youth” or “the looter kids”) submitted a press-release in which they address their families and try to convince them of the legitimacy of their participation in the protests as politically-conscious adults:

To Our Dear Families:

We are a belittled and mocked generation notorious for being apolitical....We are a generation ninety percent of whom have never taken part in an ideological struggle and thought of street protests as futile and unnecessary obstacles....Nobody was expecting us to learn how to engage in political struggle in such a short period of time and so effectively....We surprised you....We are aware that the situation might get tougher. But we are committed, conscious, and mindful. We do not panic, we adapt right away. We provide the help we need from each other in a matter of three to five minutes. We take care of our health and safety as much as we can. You’d be surprised, we are taking good care of ourselves possibly for the first time. Because we are aware that we are needed in our most healthy, robust, energetic, and sober state. The exuberance of our solidarity is immensely romanticized; but we are not carried away by it, we are very clearheaded.... So, what can you do [as our families]? Please follow the lists of urgently needed items and equipment, and try to send items related to security and urgent care rather than food and drinks. Please do not let them scare you, that’s what they want most....Trust us, support us!...

Kisses,

Your marauder kids.

Rather than being concerned about the reaction of their families and the shame they could be made to feel through family disapproval and rejection, this group of protestors sought their families’ support and respect for their political activism as conscientious adults.

Soon, an anonymous group of mothers responded to the politicians’ hailing. However, they did not follow their advice. Nor did they ask their children to come home. Instead, they fulfilled their kids’ request for support by coming down to Taksim Square and forming a human chain around the protestors to ward off the police. Mothers were in Taksim not only to show their support for their children, but also to display their own political activism. Holding hands, they chanted slogans such as “Mother power against the governor,” “Resist my child, your mama is here,” and “Don`t touch our children,” as well as “Abdullah Cömert is our child too,” in memory of the protestor alleged to have been shot in the head by the police in Hatay. By participating in the protests alongside their children, these mothers were defying the conventional notions of motherhood, according to which mothers would be expected to stay home and worry about the safety of their children.

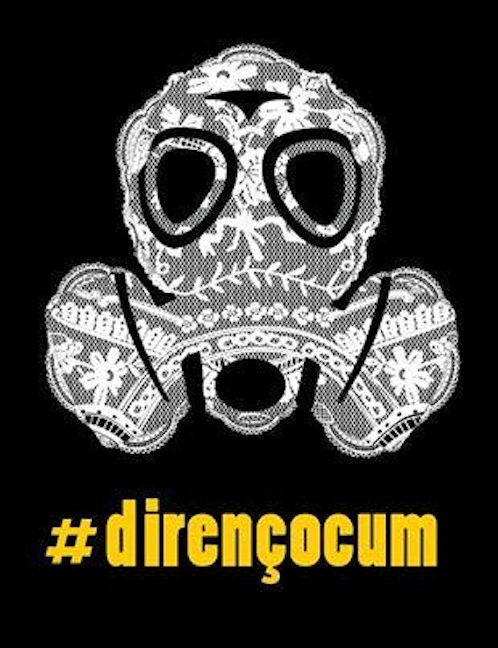

After the mothers’ participation in the protests, Internet memes that build on yet subvert traditional notions of motherhood circulated widely on social media sites. One of these memes was the photo of a woman preparing anti-tear gas solution for her children. The caption read, “An average Turkish mother nowadays.” Another meme depicted a gas mask made of lacework, a popular craft and pastime activity often attributed to mothers in Turkey. The hashtag attached to the image read, “#dirençocum” “[#resistmychild].”

[Left: A mother preparing an anti-tear gas solution for her children attending the protests. Photographer unknown, via Ergin Koçyıldırım’s googleplus page. Right: Gas mask made of lacework. Artist unknown. Image via Funda Alpaslan Talay’s twitter account.]

[Left: A mother preparing an anti-tear gas solution for her children attending the protests. Photographer unknown, via Ergin Koçyıldırım’s googleplus page. Right: Gas mask made of lacework. Artist unknown. Image via Funda Alpaslan Talay’s twitter account.]

Recently, the trailer of a documentary entitled “I Found a [New] Slogan: My Mom Is Beside Me” has been circulated on social media. The documentary, which has not yet been released, voices the opinions of the families, especially the mothers of protestors, about their children’s participation in the Gezi Park protests. One mother says that, upon seeing the news, she called her daughters and “told them to head out and go to Gezi [Park].” Some of these mothers even joined the protests alongside their children. A young girl says, “holding hands with my mother, we ran away from pepper spray.” A chuckling mother says, “We haven’t tasted the pepper spray yet, that’s the new vogue. Back in our day, we savored a good amount of police batons, though.” Despite the prime minister’s warnings about holding parents responsible for any detriment to their children’s safety, these mothers state that they do not feel intimidated. While rolling dolmas, a rural migrant mother states, “I’m not scared because my children won’t do anything that would cause me to feel scared.” Another mom says, “In the past, whenever I saw [on television] even a small protest attended by a handful of people, I would call [my daughter] and ask her to come home right away. But now, I tell her to take her gas mask and go to the protests.” A young woman expresses her astonishment about her mothers’ support: “My mom is very interesting. She told me ‘It would’ve never occurred to me that I’d be preparing an anti-tear gas solution for [my daughter].’”

In general, all the mothers depicted in this documentary seem to be proud of their children’s political activism. An impassioned mother states, “Who are these kids? These are our children who are bright like diamonds and brave like lions.” Reversing the commonly held notion that children should follow in their parents’ footsteps, another mother suggests that their kids “performed something really meaningful. I wish we could take them as an example.”

Another group of mothers who have defied the government’s request/order to bring their kids home consists of those whose children are alleged to have been killed by the police during the protests. These mothers are valorized by self-proclaimed revolutionary leftists as exemplars for sacrificing their children for the revolution and opposing the government’s understanding of appropriate parental conduct. One prominent example is the mother of Ethem Sarısülük, an activist who was wounded in the head and died during clashes in the capital city of Ankara. In an interview, she protested the detainment of her son’s friends for attending his funeral and the state’s perception of these young people as criminals. She requested that parents support their children by participating in the protests.

As Ethem’s mother, I call out to all mothers and fathers. Go to the Square and stand beside your children. Prevent [illicit] detentions. Why are they keeping [our kids] under custody? Our kids didn’t do anything [wrong]. Is it a crime to attend Ethem’s funeral? Is it a crime to be his friend...is it a crime to visit me at my house? If our children are criminals, they should lock us up too....You locked up our kids. Either let them out or lock us up too so that we can stand beside our children.

NOTES

[1] For an analysis of how the Turkish state and its rulers, including Erdoğan, have tended to view themselves as the “father,” see Fatih Doğan, “Devletin Babalıkla İmtihanı: Gezi Direnişi,” Birikim (27 June 2013).

[2] Michel Foucault, “Governmentality,” in The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, ed. Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller (London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991), 92.

[Part two of this article can be found here.]